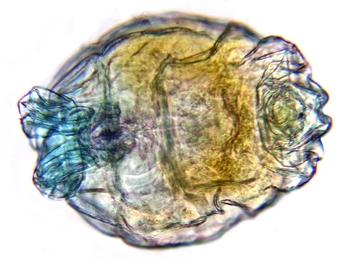

So much exists there, from soaring curlews to scurrying voles; life finds a way to survive in the wet and cold. They are the organisms we can easily see though: what about the tiny, microscopic stuff living within the sphagnum? How much life exists beneath our feet? The answer… a shed load!

From a human perspective, blanket bogs can seem pretty flat, especially without tall trees leading our eyes from the earth to the skies and giving height to the landscape. However, they are incredibly varied and complex on the microscopic scale. The undulating hummocks of sphagnum may seem small to us (and the curlews), but from the perspective of the myriad insects and microbes that inhabit them, it must feel like the Himalayan mountain range – some hummocks can be 1m tall! From the saturated ground below to the mighty heights of the domed sphagnum hummocks, this huge variation in structure is the stage for just as much of the life and drama that exists at larger scales.